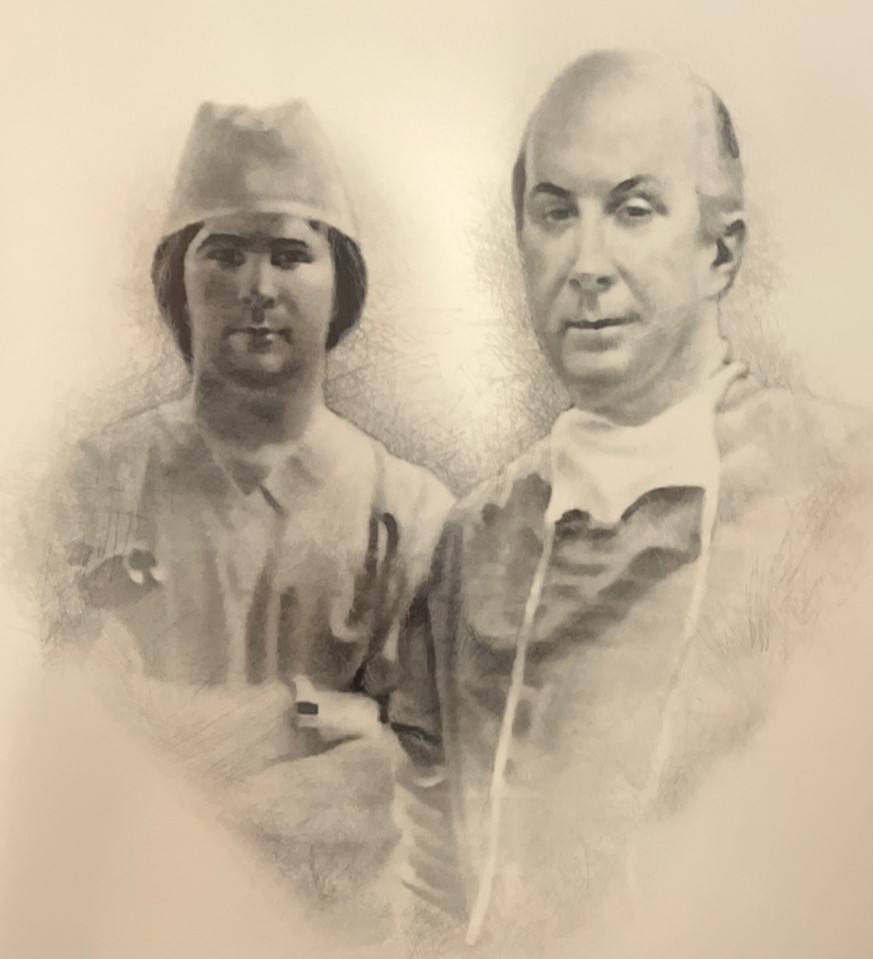

My Father, Alston Callahan, MD

My Father, Alston Callahan, MDAt the age of 26, my dad’s first job was joining his half-brother Edley Jones, MD, in an EENT practice in Vicksburg, Mississippi. However, he soon began yearning for a bigger challenge and moved to the big city of Jackson, Mississippi. This was 1937, and my dad was a single man living in a YMCA apartment while practicing ophthalmology, which mainly consisted of performing refractions with loose lenses. In 1938, he became the first ophthalmologist in the state of Mississippi to become certified by the American Board of Ophthalmology.

Dad enlisted in the U.S. Air Force but soon learned that the U.S. Army was to implement specialty care hospitals across the country to handle the head and neck casualties from the War. He knew he wanted to be a part of this medical network, and he set his sights on Northington General, located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. It was slated to be a Southeastern tertiary care hospital with 400 beds for facial, head, and neck plastic casualties.

The dilemma was that he was in the Air Force, not the Army, and had to somehow get transferred to the Army. After much consideration, he concluded that the only way he could do this was to tell his commanding officer that he was afraid of flying (even though he had previously earned a private pilot’s license). Word spread down the line that Callahan was trying to bamboozle the armed services, and because of this, his new commanding officer decided to deploy him to the South Pacific to punish him.

Looking up and down the chain of command, he realized that the superior commanding officer in his district was none other than his Tulane professor, Dr. (now Colonel) Mims Gage, who fondly remembered “Mr. Edema” and who conveniently outranked the army officer who was sending Callahan to the South Pacific. So, Dad appealed to Gage to intervene and reverse his orders, and this came through just in the nick of time, so he was placed in the U.S. Army Hospital in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, instead of the South Pacific. This event altered his future forever.

Now in Tuscaloosa, married and a father, Dad, and his colleagues worked furiously in surgery three days a week; the clinic was also three days a week, and there were conferences on Sunday. Patient presentations were enhanced by illustrations and photographs that the Army photographers took of the injuries, often with preop and postop results. This was a kind of “grand rounds” and Dad and his colleagues confronted each other just as fiercely in this arena as the soldiers did on the battlefield. I once asked Dad just how busy he was. He responded, “Mike, the wounded soldiers were shipped in so rapidly that we could hardly catch our breath. The plastic surgeons and oral maxillofacial surgeons did not have time to handle many of the patients, so we ophthalmologists began to learn how to best care for various orbital and adnexal injuries. Because of the volume, we could try various techniques to see which one was the best, so in short order, we learned how to repair these injuries in as few steps as possible.”

Now in Tuscaloosa, married and a father, Dad, and his colleagues worked furiously in surgery three days a week; the clinic was also three days a week, and there were conferences on Sunday. Patient presentations were enhanced by illustrations and photographs that the Army photographers took of the injuries, often with preop and postop results. This was a kind of “grand rounds” and Dad and his colleagues confronted each other just as fiercely in this arena as the soldiers did on the battlefield. I once asked Dad just how busy he was. He responded, “Mike, the wounded soldiers were shipped in so rapidly that we could hardly catch our breath. The plastic surgeons and oral maxillofacial surgeons did not have time to handle many of the patients, so we ophthalmologists began to learn how to best care for various orbital and adnexal injuries. Because of the volume, we could try various techniques to see which one was the best, so in short order, we learned how to repair these injuries in as few steps as possible.” Following the surrender of the Axis Powers, my dad, who was located in Birmingham, Alabama, was offered the Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. It was soon apparent that a private eye hospital, much like what was created in the Army, could prosper and become more efficient, separate from the University. The Eye Foundation Hospital was created and admitted the first patients in 1963. An ophthalmology residency was approved by the American Academy of Ophthalmology in 1965. In 1999, the Eye Foundation Hospital was named the Callahan Eye Foundation Hospital.

Following the surrender of the Axis Powers, my dad, who was located in Birmingham, Alabama, was offered the Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. It was soon apparent that a private eye hospital, much like what was created in the Army, could prosper and become more efficient, separate from the University. The Eye Foundation Hospital was created and admitted the first patients in 1963. An ophthalmology residency was approved by the American Academy of Ophthalmology in 1965. In 1999, the Eye Foundation Hospital was named the Callahan Eye Foundation Hospital.