|

|

|

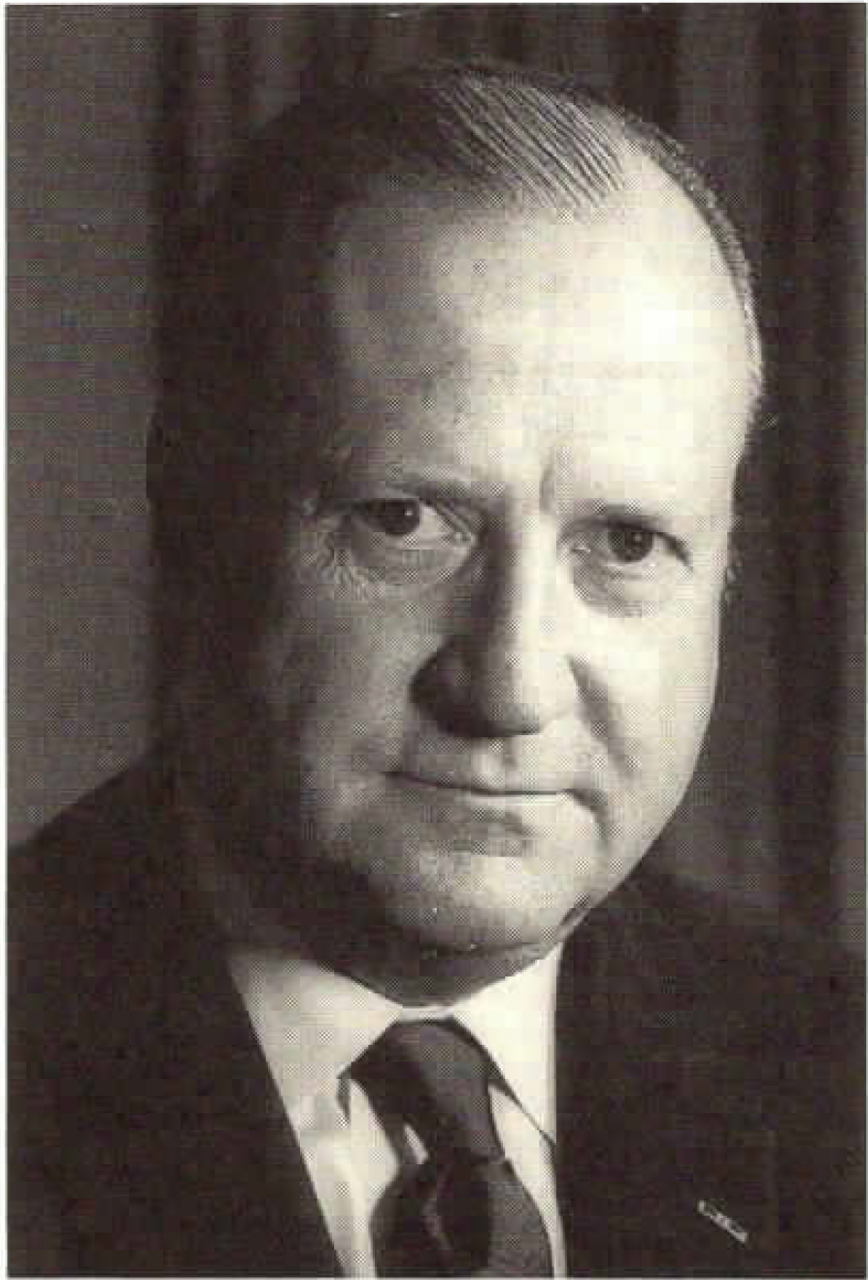

Byron Capleese Smith was a renowned pioneer in Oculoplastic Surgery. Born in Tonganoxie, Kansas, in August of 1908, he received his B.A. and M.D. from the University of Kansas in 1931. Early in his career, he trained in psychiatry at Topeka State Hospital from 1931-34. Knowing his personality, I suspect that he quickly realized psychiatry was not his calling. Byron continued on to New Haven Hospital, completing a residency in general surgery in 1938. Finally, he completed a two-year residency in ophthalmology at The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary in 1940. Byron realized that WWII was imminent and that many soldiers would need reconstructive surgery. Anticipating military service, he spent much of the next year working with Wendell Hughes, who had a large oculoplastic practice. Byron’s background and skills resulted in him being named Chief of Ophthalmology and Plastic Surgery of the 1st General Military Hospital of England and France for the duration of the war and earning a Bronze Star. After the war, Byron returned to New York City and affiliated with Dr, John Converse to begin an oculoplastic clinic at the Manhattan Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital. He was soon named Chairman of Ophthalmology and Director of Oculoplastic Surgery. Ever the consummate teacher, he realized few ophthalmologists had significant knowledge or training in lid, lacrimal, and orbital surgery, and so he began a fellowship program in 1960. In the early 60’s there was no formal structure to ophthalmic fellowships. No match. No specific requirements of the fellowship director. At the time there were three significant oculoplastic fellowships and Byron’s was probably the least structured. To be a fellow in Byron’s fellowship was a simple process. You called and asked—the answer was always the same: Yes. Come and stay as long as you like. What this really meant was come and watch me do surgery. Therefore, on any given day there might be six to eight people gathered around his operating table. But there was a catch, and that was that at any given time one or occasionally two individuals would be designated as Principal Fellows with the additional privileges of scrubbing in on surgeries, making rounds, and going with him to evaluate his office patients. The process of becoming a Principal Fellow was somewhat random. In my case, I called in the spring of 1968, and he stated that he was without a fellow and if I came soon, I could be Principal Fellow for as long as I stayed. My residency chairman allowed me to leave early, and I arrived in New York on May 1st, 1968. Times were different. I had no New York state license, no malpractice insurance, no salary or income, no hospital privileges. With no place to stay, I ended up at the 41st Street YMCA for 5 months. I worked up hundreds of his patients, photographed most of them in the office and in the OR (no releases), scrubbed on approximately 200 cases and acted as principal surgeon on exactly ONE case. Byron Smith was a gentleman and an educator, in the truest sense of the word. The opportunity to observe his surgical expertise and pick his brain changed my life. He was a quick, innovative, and exacting surgeon with a constant intellectual curiosity. If you were lucky enough to hear one of his thousands of lectures, it would be beautifully illustrated and impeccably organized. He treated his fellows like his own blood. You were invited to cultural events, worked out with him at his club, dined with him at the best New York restaurants, drank with him in local bars, and all the while he would be dropping pearls. If he was going to be away lecturing, as he was frequently, he arranged for you to spend the day with the internationally renowned surgeons of Manhattan including Reece and Ellsworth for orbital surgery, famed corneal transplant surgeon Ramon Castroviejo, and observing Mohs surgery at Belleview Hospital. Byron hunted and fished the world over, frequently in association with an international lecture. But his favorite pastime was instigating a GREAT party. Many of his fellows found this out years after their training when they invited him to lecture in their community. After he had trained a few fellows, the Byron Smith Study Club was organized and met annually during the Academy Meeting. Byron set the standard for the meeting, preferring a fine restaurant as the site, (sometimes he required black tie!), and he expected attendees to give a paper on a personal surgical complication or difficult diagnostic case. Some years you had to tell a raunchy joke prior to your presentation! Things were different in Manhattan before ASOPRS, but Byron was ahead of his time. As noted by The New York Times, Byron Smith passed away December 5th, 1990, at the age of 82-years-old. Affectionately referred to as Lord Byron of Broadway, his legacy survives based upon his six books, influential lectures, many publications, and keen foresight. He trained many of the second generation of Oculoplastic Surgeons including, remarkably, seventeen of the first 25 ASOPRS presidents. |

Mar

21

Share this post: